Canadian Glass Worth Collecting

By Louise Swan

Reprinted from The Hobstar, July 1986

Facts concerning lead glassware cut in Canada are hard to find. Little has been written on the subject. Certain collectors of American Brilliant Period glass are wary of buying Canadian ware. They need not worry if they follow the same criteria as when choosing good U.S. pieces. One must seek a clear blank of good color and accurate cutting. Much Canadian glass resembles U.S. ware because cutters often went to Canada after training here. They used U.S. blanks as well as European, such as Baccarat, but some of our well—known companies also used European blanks occasionally.

No heavy lead crystal suitable for cutting was ever manufactured in Canada, with few exceptions. Burlington Glass Works in Hamilton, Ontario (1875—1909) is said to have made some on special order. Staple products in the 1840s and 1850s were window glass and bottles. The Year Book of 1876 has figures proving that in that year Canadian firms supplied the home market with nearly a million items pressed in soda—lime glass. High customs duties on imports (30% in 1891) protected domestic production.

In addition to common bottles, pressed and blown tableware (colored and clear), paperweights, lamp chimneys (sandblasted and engraved), and cuspi— dors, craftsmen made hats, canes, and drapes (glass ornaments connected by glass chains) as whimseys during the lunch hour. This was the situation during the last quarter of the nineteenth century in our neighbor to the north, while our firms, such as Mt. Washington, New England, Dorflinger, Hawkes, and others were cutting large quantities of brilliant ware.

In addition to common bottles, pressed and blown tableware (colored and clear), paperweights, lamp chimneys (sandblasted and engraved), and cuspi— dors, craftsmen made hats, canes, and drapes (glass ornaments connected by glass chains) as whimseys during the lunch hour. This was the situation during the last quarter of the nineteenth century in our neighbor to the north, while our firms, such as Mt. Washington, New England, Dorflinger, Hawkes, and others were cutting large quantities of brilliant ware.

Canadian pieces found for sale now date mainly from 1900 to 1925. Many small shops and a few large ones were set up after 1900. Polishing by acid was done in most shops, but Gundy-Clapperton used wooden and felt wheels as late as 1913.

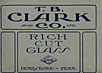

Gowans,was listed crockery and Kent & Company of Toronto as a wholesale dealer in glassware in 1897. In 1900,G.H. Clapperton, after a ten-year apprenticeship with Libbey, went to work for Gowans, Kent, where he cut the first brilliant cut glass in Canada. The trademark is ELITE-on-a-maple—leaf. (See figs. 1 and 2)

In 1905, Clapperton started his own business, designing and cutting all patterns himself. In 1906, he was joined by N.F. Gundy under the name Gundy-Clapperton Company. For about ten years, the trademark was GCCo-in-a--shamrock, then was changed to C-in-a-shamrock. In the early 1920s, the mark was omitted from smaller items. Blanks came from Baccarat of France, Val St. Lambert of Belgium, Libbey, Fry, Union Glass (Mass.), and Dorflinger.

The vase (fig. 3) is signed BIRKS in addition to the Gundy-Clapperton trefoil, an instance of the common practice of adding the distributor’s name to that of the cutter. I have also seen 0. B. ALLEN, VANCOUVER, and DINGWALL above or below the cloverleaf.

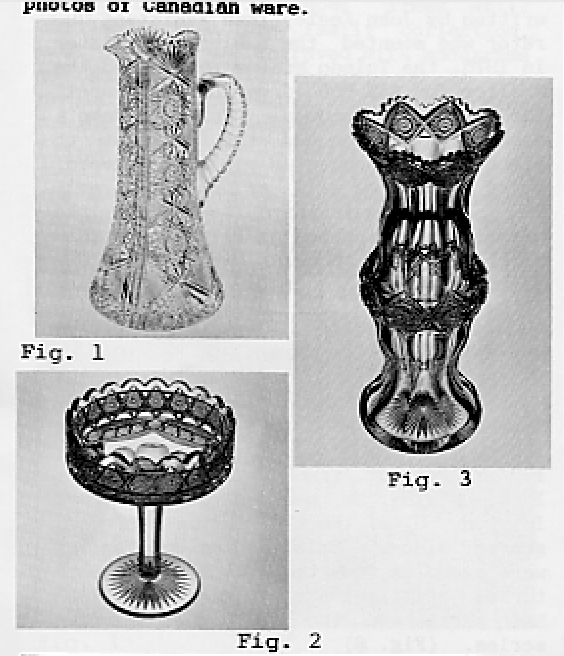

The signed tray (fig. 4) in "Hob Star" is the highest in quality of cutting and blank, while the cream and sugar set (fig. 5) is nicely decorated by stone engraving.

Roden Brothers started in Montreal in 1879 as silversmiths and jewelers. They opened branches in Toronto and other cities in Canada and in London after 1900. Some of their glass is signed PORT/&/MARKLE—in—a-circle. We do not know when they started cutting geometric and floral designs on lead glass, but the trademark, an ornate R-with-flankinglions, is dated 1901.

Two patterns nearly identical with those of Meriden (Connecticut) were registered in November, 1910: "Old Irish" and "Norman," similar to "Alhambra." The signed berry bowl in "Edna" (fig. 6) compares favorably with Egginton glass.

We have discovered facts concerning the following cutting shops:

St. Lawrence Glass Company of Montreal (1867-1875) advertised "the finest kinds of pressed and cut Flint Glassware," yet ads mentioned only cut lamp shades, and "flint" meant "colorless."

Nova Scotia Glass Company of Trenton (1881—1892) was decorating pressed and mold-blown pieces with both cutting and engraving. Cutters were mainly Bohemians.

Robert McCausland, Ltd. of Toronto (1856—?): artists in stained glass for churches. They also cut glass. George Phillips & Company, Ltd. Of Montreal (1907—?) and these in Ontario: Belleville Cut Glass Company (1912—?); Lakefield Cut Glass Company (1915—1920), which sometimes marked glass with a small Union Jack; and Ottawa Cut Glass Company (1913—?)——all were active.

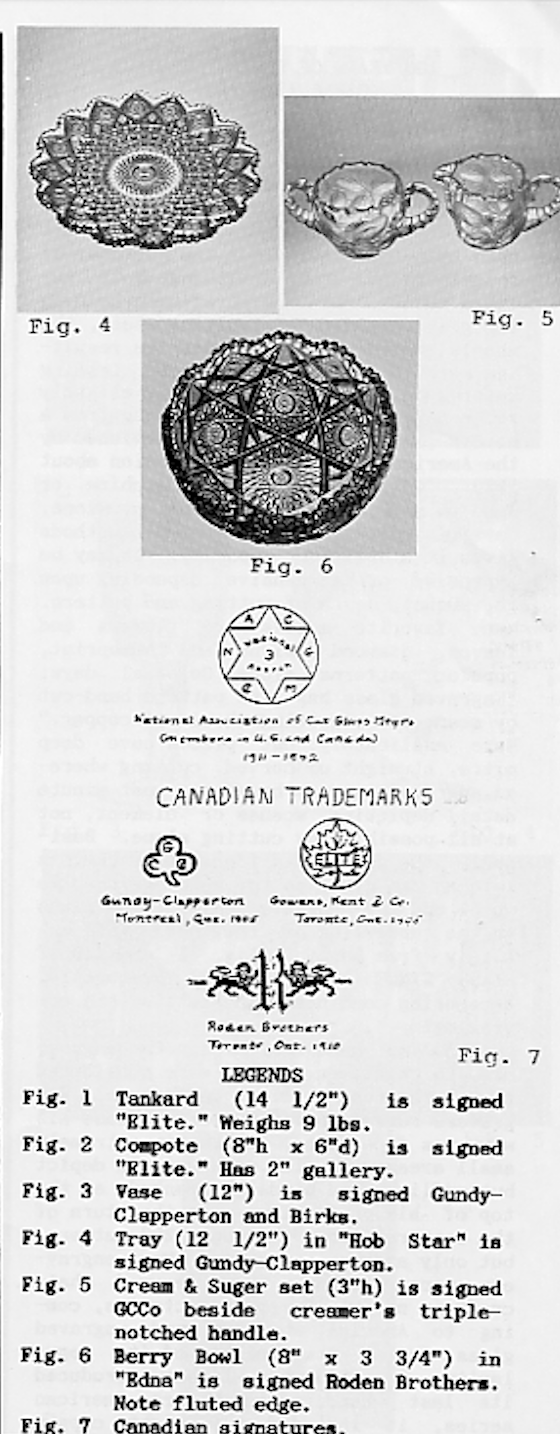

A trademark with NACGMCo, arranged around a circle between points of a six— pointed star with a number in the center, has been called a Canadian mark (fig. 7). NATIONAL was above and ASSOCN below the number. Number 3 was assigned to Phillips Cut Glass Company in Montreal. The symbol was adopted in 1922 by a group called National Association of Cut Glass Manufacturers, organized in Buffalo, N.Y., 17 August 1911; incorporated in Pennsylvania, 9 March 1921. It remained active until 1942. Its purpose was to uphold standards. Of eighty-four members recalled by Raymond Fender (secretary from beginning to end) for Albert Christian Revi, George Phillips Company and Gundy-Clapperton were the only Canadian firms. See pp. 461—3 in Revi’s American Cut & Engraved Glass for a list of prestigious American firms who belonged, and pp. 266-71 in my American Cut & Engraved Glass of the Brilliant Period (published in 1988 by WallaceHomestead) for additional details and photos of Canadian ware.

A trademark with NACGMCo, arranged around a circle between points of a six— pointed star with a number in the center, has been called a Canadian mark (fig. 7). NATIONAL was above and ASSOCN below the number. Number 3 was assigned to Phillips Cut Glass Company in Montreal. The symbol was adopted in 1922 by a group called National Association of Cut Glass Manufacturers, organized in Buffalo, N.Y., 17 August 1911; incorporated in Pennsylvania, 9 March 1921. It remained active until 1942. Its purpose was to uphold standards. Of eighty-four members recalled by Raymond Fender (secretary from beginning to end) for Albert Christian Revi, George Phillips Company and Gundy-Clapperton were the only Canadian firms. See pp. 461—3 in Revi’s American Cut & Engraved Glass for a list of prestigious American firms who belonged, and pp. 266-71 in my American Cut & Engraved Glass of the Brilliant Period (published in 1988 by WallaceHomestead) for additional details and photos of Canadian ware.